Evening rush hour often brings bumper-to-bumper traffic just beyond the front door of Jackie Green’s downtown bike shop.

It’s a scene that bothers Green, a staunch supporter of smaller streets, slower speeds and fewer cars.

“We have lost control of the safety of our streets,” Green said during a recent interview at his shop.

Regaining that safety is, in part, what’s driving him to continue fighting a pair of traffic citations he received while riding a bicycle along Third Street more than a year ago.

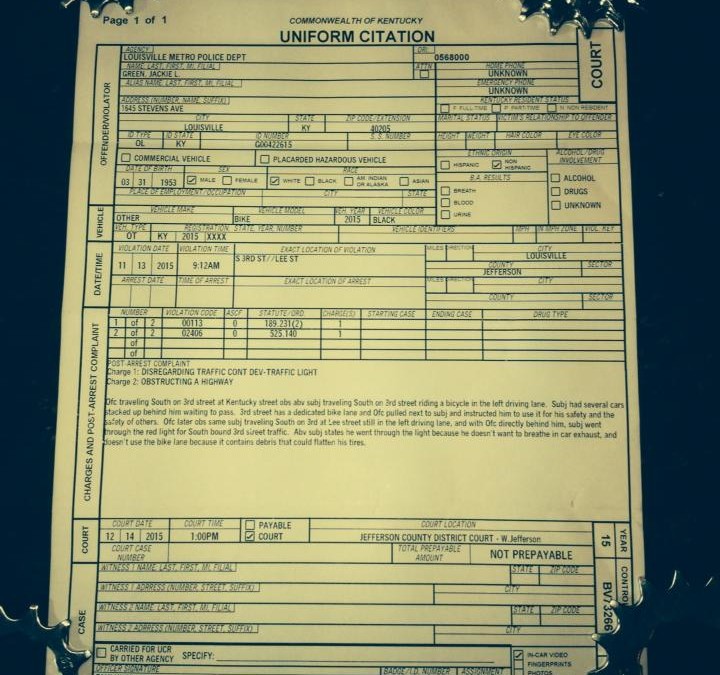

Green ran a red light. He’s charged with disregarding a traffic signal and obstructing a highway. The latter carries a penalty of up to 90 days in jail.

He dismisses both charges, saying he ran the light for his safety. But local prosecutors aren’t buying it.

A spokesman for the County Attorney’s office says more than 100,000 cases come through District Court annually, and they work them all.

“This man wants his day in court, and we’re there to make sure he gets it,” said Josh Abner, a spokesman for County Attorney Mike O’Connell.

For Green and his attorney, Ryan Fenwick, who’s also an avid bicycle commuter, it’s about sending a message to city officials.

“Our objective is to challenge Louisville’s urban traffic policies and to reclaim the commons,” Green said. “That’s why we are in the fight.”

More Than Bicycle Lanes

Green is a longtime cyclist and activist in Louisville. He owns Bike Couriers Bike Shop and has commuted by bike since 1975. He touts his car-free lifestyle.

“My life is lived on foot, by bicycle and by TARC,” he said.

Green has also mounted two unsuccessful bids for mayor, even challenging Mayor Greg Fischer in his most recent reelection bid.

The basement of Jackie Green’s Bike Couriers Bike Shop.

In many ways, Green is the model citizen for Fischer’s administration. He’s engaged, he rides a bike, he’s a small-business owner and he champions a sustainable lifestyle. He even received a city grant late last year to install solar panels on one of his properties.

And by continuing to fight the traffic charges, he wants to send a message to Fischer that the city should go beyond building bicycle lanes and take a more holistic approach to supporting cyclists in Louisville — starting with how local traffic laws are interpreted.

“If the law does require that a cyclist behave like a driver of a 2-ton vehicle, that’s an absurd law,” he said.

Green said a bicycle is vastly different from a vehicle and should be afforded the leeway to operate differently on city streets. This includes, he said, occasionally moving through an intersection before the light turns green.

Metro Continues To Invest

Green’s effort highlights the role laws can play in the promotion of cycling in cities.

Louisville Metro government officials have made regular budget allocations of up to $300,000 to fund the construction of bicycle infrastructure, including bike lanes and bike racks, in recent years. It’s part of a broader push to make the city more bicycle-friendly, which is an attractive feature for attracting young, skilled workers to the area.

Certain policy changes can also help that cause, according to the League of American Bicyclists. Some of these issues include easing restrictions on when cyclists are allowed to proceed through red lights and where cyclists are required to ride on the roadway.

Chris Glasser is executive director of the local cycling advocacy group Bicycling for Louisville. He commends Green’s effort and acknowledges there is validity in the argument.

But Glasser’s group thinks improved design of city infrastructure will help promote cycling and is focused there.

“I don’t see it as a rights question,” he said. “I see it as a smarter engineering solutions question.”

Glasser said timing traffic lights to be friendlier to pedestrians and bikes could reduce the need to ride through red lights, while smaller streets could promote slower traffic.

Green agrees there’s plenty of room to improve the city’s built environment for cyclists. Addressing those needs, he said, could make the streets safer for bikes, as well as pedestrians and motorists, alike.

But he sees his case as a proving ground for city leaders’ willingness to support cyclists here.

“If I’m found guilty, it sends the wrong message to everybody,” he said. “It tells people that Louisville is not interested in making the commons safer — not for cyclists, not for pedestrians, not even for motorists.”